From the Scott County Scene, April/May 2020

During the County’s 2040 Comprehensive Planning process, there was healthy debate among residents, landowners, developers, and elected officials on sustainable land use and density policies in the rural areas. Some wanted more housing in the County’s longstanding farmland preservation areas, while others in the more developed part of rural Scott County wanted to move away from small-lot cluster housing development to larger 10-acre lots.

In both situations, there was good discussion on how changes in rural density policy could impact the cost to deliver public services to these areas, such as roads, public safety, social services, and school busing. Unfortunately, these discussions were not rooted in any real data analysis or systematic method to evaluate fiscal impacts associated with different land uses and densities.

One of the key challenges the County faces as it continues to grow is understanding the fiscal impacts associated with different types of land use, particularly in rural areas of the County that are experiencing rapid growth. The fiscal consequences of different land uses vary significantly, in terms of both the amount of tax revenues generated and the cost of providing local government services.

During its recent partnership with University of Minnesota’s Resilient Communities Project, Scott County collaborated with students and faculty to help uncover these fiscal impacts of the County’s three broad rural land-use categories: Agricultural Preservation (with a residential density of one housing unit per 40 acres), Rural Residential (residential densities ranging from one housing unit per 2.5 to 10 acres), and Rural Commercial/Industrial.

“We thought this was a great opportunity to tap into the University’s insight, knowledge, and energy to conduct this type of analysis,” said County Planning Director Brad Davis. By reorganizing publicly available data on how Scott County raises and spends money, Davis said he hoped the University could help answer the question of which land-use types tend to “pay their own way.”

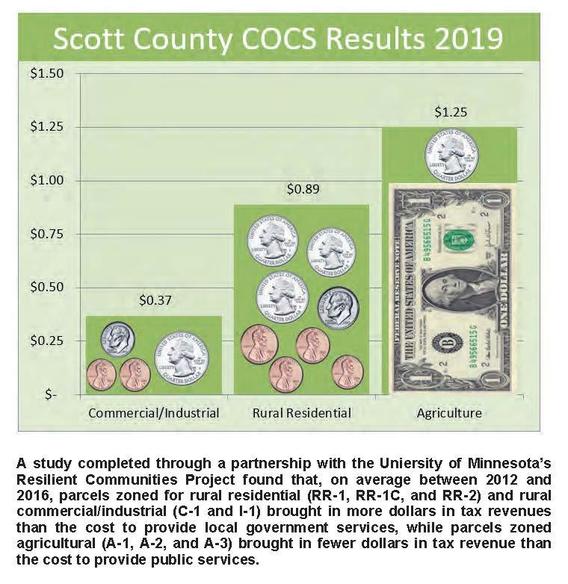

In February, the results of the U of M student study were presented to County Commissioners. The study found that, on average between 2012 and 2016, parcels zoned for rural residential (RR-1, RR-1C, and RR-2) and rural commercial/ industrial (C-1 and I-1) brought in more dollars in tax revenues than the cost to provide local government services, while parcels zoned agricultural (A-1, A-2, and A-3) brought in fewer dollars in tax revenue than the cost to provide public services. The “cost of community services” ratios, in terms of dollars spent per dollar raised, are: Agricultural, $1.25; Rural Residential, $0.89; and Commercial/Industrial, $0.37.

Terin Mayer, the U of M Ph.D. student who conducted the study, cautioned County staff and leadership to view these results at a high level and not jump to any specific conclusions. “One might be tempted to assume this means the County should court more land uses with low ratios and shun those with high, but one should be very careful in drawing that conclusion. Because this study is only a snapshot in time, it says very little about the budget effects of any radical zoning change,” said Mayer

The cost of community services study was modeled after an approach promoted by the American Farmland Trust that has been widely used by communities across the nation. However, even with an established methodology, Meyers said that there were a lot of assumptions and decisions that needed to go into this type of analysis. “An inherent challenge of the work involved trying to think geographically about budget line items that don’t always have a geographic footprint. We were trying to figure out how much of a department’s spending went to each of the different land-use types, and it was often not obvious how to go about that task.”

The study’s ratio for agricultural lands departs from findings from most other cost of community services studies across the nation. “Our methodology included farmsteads in the income-generating revenue coming to local and county governments and schools, while national studies excluded these improvements in the revenues.” Meyer explained. “This difference in methodology changes the overall results when comparing our study to national studies, but is a methodology that in my mind is more logical and defensible when discussing the ‘true’ impacts of different density policies.”

The Commissioners picked up on the agricultural cost ratio, and asked if the three biggest County expenditure cost drivers – general government, health and human services, and public safety – are based on actual use of these services by township and city residents, and not just spread out on a per capita basis. Meyer acknowledged that there are limitations in interpolating what portion of the rural and urban population actually use specific County services. Davis said another possible driver to this ratio is on the revenue side of the equation. Agricultural properties are often enrolled in tax benefit programs like Green Acres or Metropolitan Agricultural Preserves, where the land is assessed on the agricultural value rather than the potential market value.

Davis told Commissioners that finalizing a cost of services study was a key recommendation coming out of the County’s adopted 2040 Comprehensive Plan, and the study results could help enhance some of the discussions happening at the township level around long-term road and infrastructure costs and will shape some of the discussions in the next planning cycle. “I hope the results will inform decisions made today and into the future on setting sustainable land-use and housing-density policies in Scott County’s rural areas,” said Davis.

To obtain a copy of the Cost of Community Services study or get more information, contact Brad Davis at (952) 496-8564 or [email protected].